In October 2025, Amazon announced a multi-year deal with ALSO, a Rivian spinoff, to deploy thousands of TM-Q pedal-assist cargo quads across dense US and European cities starting in spring 2026. These four-wheel vehicles haul over 400 pounds, run on swappable batteries, and operate legally in bike lanes—completely bypassing the truck regulations, congestion fees, and low-emission zone restrictions that strangle downtown delivery in London, Paris, New York, and San Francisco.

Amazon isn’t alone. UPS is testing four-wheeled eQuad cargo bikes and estimates potential savings of millions annually from e-cargo integration. FedEx launched cargo bikes in Toronto in 2019, expanded to over 43 bikes across seven Canadian cities by 2021, and operates from shared micro-hubs. DHL operates large-scale cargo bike fleets across European cities. But Amazon’s commitment to thousands of also quads, paired with 70+ existing micromobility hubs, represents the largest coordinated scaling effort to date.

This isn’t one company’s pilot—it’s proof the entire industry believes cargo quads are the economic answer to urban regulation. And it’s arriving faster than most carriers are prepared for.

Why This Is a Structural Shift, Not a Trend

For the last 20 years, the urban last-mile was a binary choice: truck or van. Cargo quads create a third option—and for the 30-40 percent of urban delivery that happens on routes under two miles, they’re increasingly the best option.

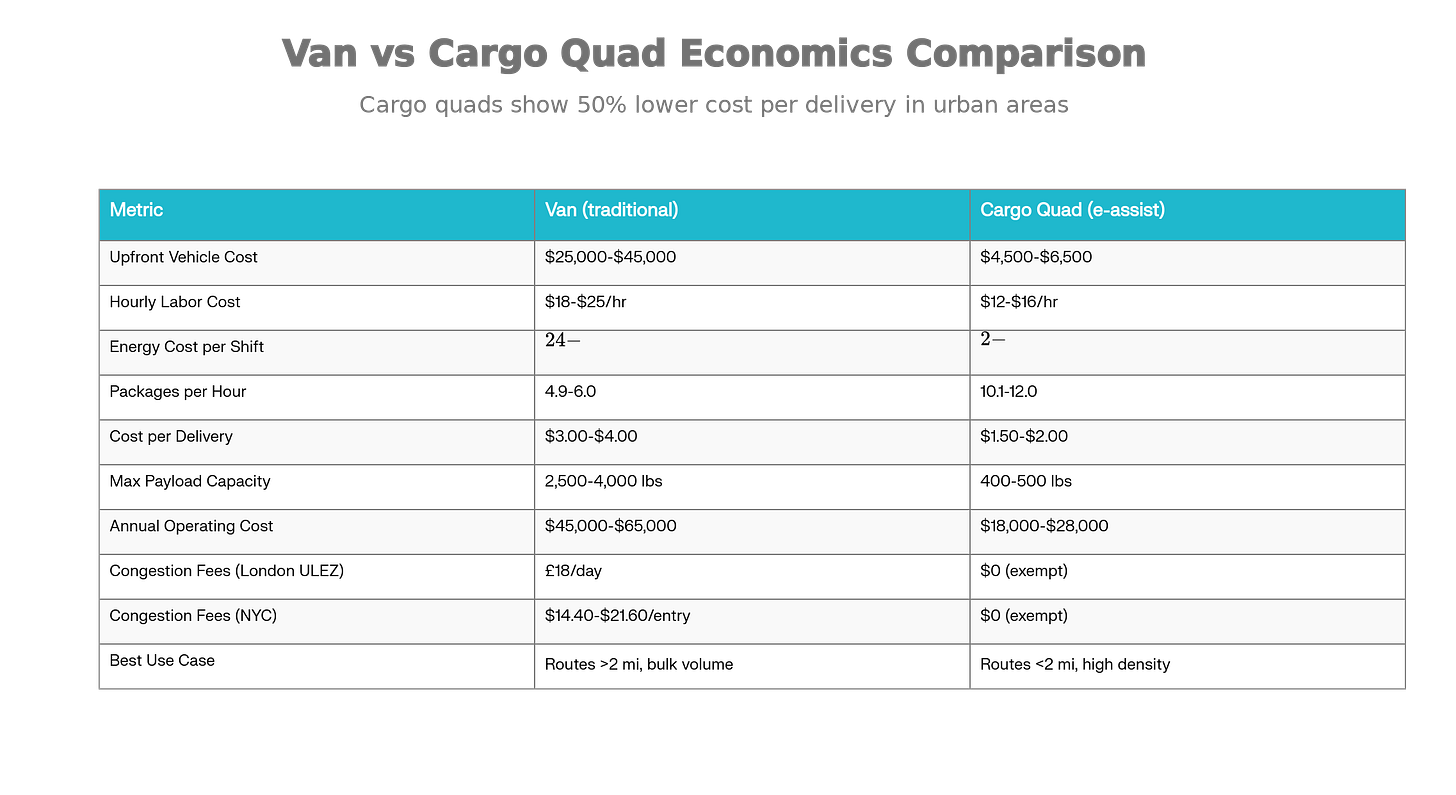

The numbers are compelling. Research from Brussels comparing cargo bikes to traditional vans shows cargo bikes deliver 10.1 packages per hour versus 4.9 for vans—more than double the efficiency. Cost per parcel drops from €1.10 for a diesel van to just €0.10 for a cargo bike. On short routes in dense cores, cargo quads eliminate the “driving and parking tax” that makes van economics break down when you’re stopping every block.

But economics alone don’t drive structural shifts. Regulation does.

The Regulatory Tailwind: From Headwind to Mandate

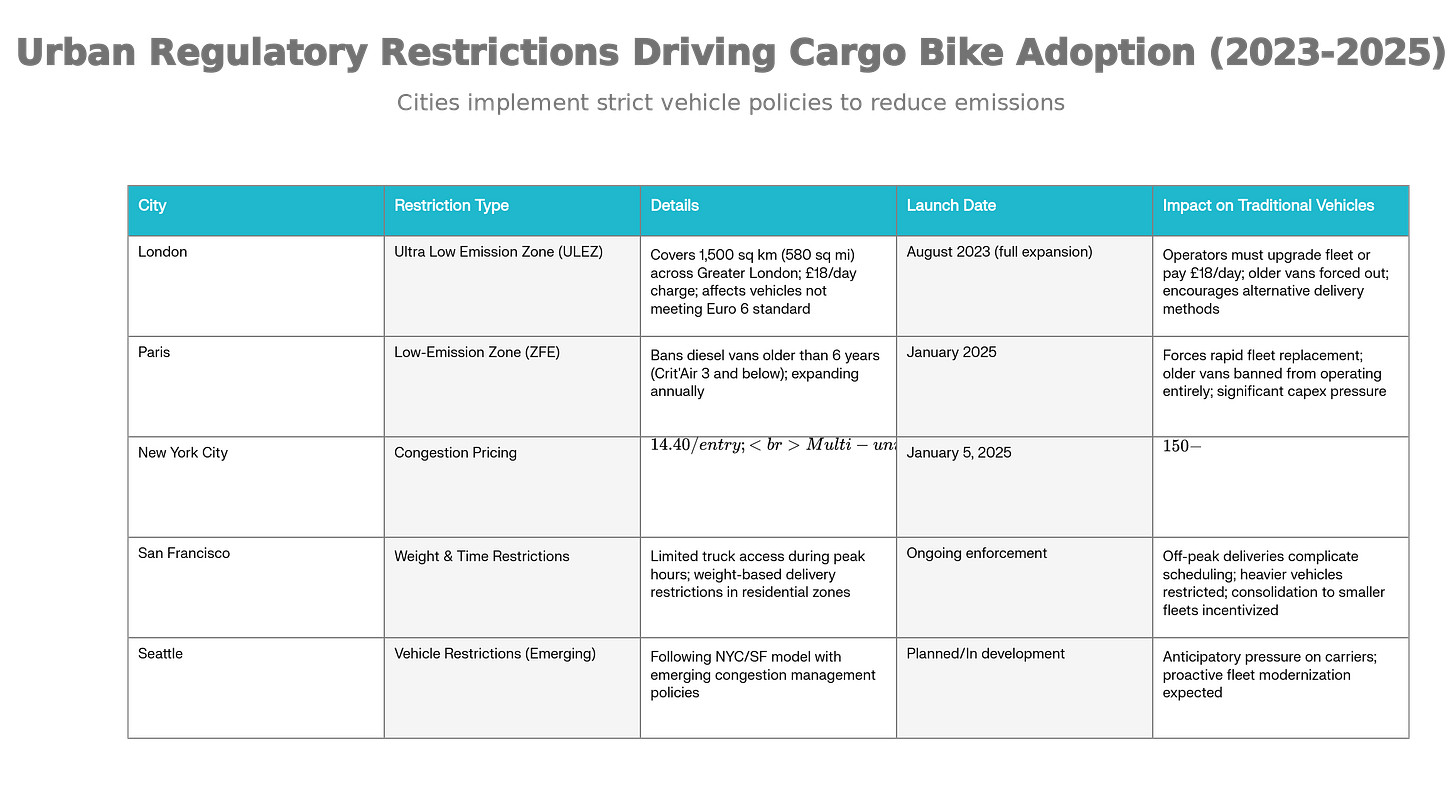

The last five years have brought unprecedented restrictions on vehicle access in major cities. These aren’t temporary experiments—cities are doubling down on climate commitments and congestion management. As they tighten, trucks and vans become structurally worse investments.

London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) expanded in August 2023 to cover 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles) across all of Greater London. Operators must either scrap older vehicles or pay £18 per day—a daily fine that kills economics on routes with thin margins. EV vans exist, but upfront costs start at $35,000-$45,000.

Paris’s Low-Emission Zone bans diesel vans older than six years, effective January 2025. In a city where delivery fleets average 7-8 years old, this forces rapid modernization or operational shutdown. Older vans can’t operate at all—there’s no “pay a fee” escape hatch.

New York’s Congestion Pricing, launched January 5, 2025, charges trucks $14.40 to $21.60 per entry into Lower Manhattan, depending on vehicle size. For a typical delivery route with 20-30 stops, that’s $150-$200+ per vehicle per day in congestion fees alone. The fee stacks on top of fuel costs, tolls, and parking.

San Francisco, Seattle, and other US metros are following suit with cargo-restricted hours and vehicle-weight limits. Once a major city implements congestion pricing or emission zones, others inevitably follow—both for revenue and environmental targets.

Regulation doesn’t just allow quads. It makes quads the rational choice. They’re not low-emission; they’re zero-emission. They’re not classified as vehicles; they’re bikes—which means they don’t pay congestion fees, don’t need parking, and don’t clog streets. A $4,500-$6,500 cargo quad costs 10% of a diesel van, runs on $2-$3 in battery swap costs per shift, and operates in the only unregulated space left: bike lanes.

Operational Reality: What Works, What Doesn’t

The temptation is to declare cargo quads a silver bullet. They’re not. Experienced logistics teams will immediately spot the constraints.

Capacity Limits Are Real: A cargo quad hauls 400-500 pounds. A van carries 2,500-4,000 pounds. On a route with 200+ stops, you need multiple quad runs or a consolidated van run. For bulk volume or oversized items, vans are non-negotiable. Cargo quads work for parcels under 10 pounds in high-density zones—the 30-40 percent of urban volume that fits those parameters. Beyond that, you’re back to vans.

Weather Is Manageable, Not Irrelevant: FedEx’s Toronto couriers insisted on riding their cargo bikes in six inches of snow—they covered more stops faster than they did with vans. However, extreme weather (ice storms, heat waves, hurricanes) still impacts operations. Quads don’t “bypass” weather; they handle typical conditions better than vans do.

Infrastructure Complexity Is Underestimated: Amazon’s 70+ micromobility hubs seem like a simple extension of existing networks. They’re not. Micro-hub economics require high-volume throughput to justify setup costs, staffing, and overhead. Prague succeeded by having multiple logistics firms share city-provided hubs to split costs. Amazon can absorb these costs; smaller competitors can’t. Additionally, traditional routing software is “designed for vans picking up at the start of the day and completing eight hours of deliveries,” but cargo bikes require “dynamic routing approaches” because they can’t handle eight hours of deliveries per run. Software overhauls are invisible but expensive.

Maintenance & Reliability Gaps Exist: Cargo bikes “emerge from the bicycle industry, not automotive manufacturing,” creating “challenges around reliability, maintenance, and fleet management” that automotive logistics teams have solved over decades. You can’t rely on a nationwide van maintenance network; you’re building new supply chains from scratch.

Regulatory Uncertainty Remains: New York limits cargo bikes to 15 mph and 48 inches wide. Other cities lack clear frameworks entirely. As cargo quad volumes grow, regulatory scrutiny will intensify—safety standards, stability testing, and worker classification will become contentious. Plan for regulatory surprises.

Worker Rights Vulnerability: Cargo bike couriers have historically faced poor working conditions and misclassification. As this model scales, labor standards will come under pressure. Budget for wage and benefits implications.

These constraints don’t kill the business case. They shape it. Quads dominate routes under two miles in dense urban cores with high stop density. They’re irrelevant for regional delivery, suburban routes, or anything requiring a major payload. The winners won’t replace vans with quads—they’ll run hybrid fleets optimized for each vehicle’s economics.

How This Rewires Three Layers of Logistics

Layer 1: Fleet Mix Becomes Fragmented and Optimizable

For 20 years, the urban last-mile was a standardized model: buy or lease vans, hire CDL drivers, and optimize for volume and speed. Quads smash that template.

Now shippers and carriers need three vehicle classes with three cost profiles, three driver profiles, and three regulatory pathways:

Long-haul trucks: 20+ miles, full truckload, regional, and cross-regional

Delivery vans: 2-20 miles, consolidated routes, suburban and secondary cities

Cargo quads: Under 2 miles, high stop density, urban cores

Network design becomes harder—but also more optimizable. A carrier that can route a sub-2-mile cluster of stops to a quad instead of a van saves $1.50-$2 per delivery. Multiply that across thousands of deliveries monthly, and the margin impact becomes substantial.

But it requires new IT systems, new labor management, new economic tracking, and operators who understand which tool fits which route. The logistics teams that can execute this hybrid model win. The ones that still rely on vans lose.

Layer 2: Curb Access and City Zoning Shift

Urban real estate is about to change. As cities normalize cargo quads in bike lanes, they’ll update curb regulations, loading dock priorities, and building codes.

Loading docks currently designed for 18-foot vans backing up will be reprioritized. Parking enforcement will shift to favor bike-lane logistics. Building codes will allocate space for cargo-quad loading corrals—safe zones for bikes to transfer packages from buildings. Fire codes will change to allow battery storage in building lobbies.

This isn’t radical. European pilot cities are already implementing these changes. Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and London have converted traditional delivery spaces into “cargo bike corrals” where bikes can be loaded safely.

Once Amazon normalizes quads in US metros, cities will fast-follow with curb rule changes. And that changes real estate value, site selection for fulfillment centers, and how shippers think about urban geography. A warehouse one block from a high-density retail zone becomes more valuable if access is bike-legal. One three block away becomes less valuable.

Logistics real estate teams need to anticipate this. It’s coming.

Layer 3: Pricing Power Consolidates

Here’s the hardest truth: if cargo quads deliver packages 30-40 percent more efficiently than traditional vans on urban routes, Amazon’s pricing leverage goes vertical.

Shippers will demand quad delivery on urban routes because it’s cheaper and faster. Competitors will be forced to match or lose volume. But not every carrier can absorb the capital costs of building micromobility hubs, securing bikes, and retraining operations.

The result: consolidation via technology and regulation, not acquisition. Carriers that deploy quads will command premium market share. Carriers that can’t or won’t will be relegated to longer-distance and suburban routes. The 3PLs that control micromobility and last-mile consolidate. Smaller carriers get squeezed.

This isn’t a market share story—it’s a profitability story. And the winners are determined by execution speed, not fleet size.

What to Do: Strategic Moves by Role

Shippers: Renegotiate Pricing and Routing

Build quad incentives into carrier SLAs. If your carrier offers quad delivery on urban routes, price it 10-15 percent lower than van delivery and lock it into your routing guides. This creates a financial incentive for carriers to deploy.

Update network design assumptions. Stop assuming trucks and vans are interchangeable across all routes. Build separate models for quad routes (sub-2-mile, high-density urban), van routes (2-20 miles, secondary cities), and truck routes (20+ miles, regional and long-haul). Model where quads actually beat vans, and adjust SLAs accordingly.

Pressure carriers on urban pricing. If they’re not testing quads or e-bikes, ask why. Their cost structure should be dropping 30-40 percent on short urban routes. If it’s not, they’re falling behind and will lose competitive pricing power. Make it clear you expect quads in your delivery mix by Q3 2026.

Use FreightFA tools to stress-test your carrier economics. Model quad deployment costs, labor cost shifts, and route optimization scenarios specific to your geography and volume mix. You’ll spot carriers who are genuinely planning for this shift versus those that are hoping it goes away.

Carriers and 3PLs: Pilot Immediately, Scale by Q3 2026

Deploy a 90-day pilot on your highest-density metro route. Pick one city—NYC, LA, Chicago, or SF—and deploy 20-50 quads for 90 days. Measure cost per delivery, driver utilization, customer satisfaction, and operational headaches. Don’t overthink it. Get real data.

Partner with existing operators, don’t build from scratch. Contact Also, Scobie, or local cargo bike operators. Don’t own assets—partner with them or lease fleets. Speed to market matters more than control. You need to learn operations, not invent hardware.

Rethink driver economics. Quad operators don’t need CDL licenses, safety ratings, or multi-year training pipelines like truck drivers. You can use gig labor, reduce training costs, and scale faster. But you’ll need new insurance, liability frameworks, and HR systems for a different workforce. Budget for that complexity.

Prepare for Amazon’s pricing moves. If Amazon drops urban delivery pricing by 30 percent using quads, your margin evaporates unless you match their cost structure. Quads are how you match it. This isn’t optional—it’s a survival move for carriers with dense urban routes.

Supply Chain Leaders: Model the Fragmentation

Build a three-vehicle network model for your 2026-2027 plans. Don’t assume one vehicle solves all routes. Separate truck routes (long-haul, regional), van routes (suburban, secondary cities), and quad routes (dense urban, sub-2-mile). Run financial models for each, including capital costs, labor, fuel/battery, and congestion fees.

Update carrier scorecards. Stop measuring performance by “on-time delivery” alone. Start measuring cost per package, emissions per delivery, and quad readiness. Carriers with deployed quad fleets will win on cost and environmental metrics. Benchmark accordingly.

Plan for curb access changes. Talk to your real estate and site selection teams now. How will updated city zoning affect your warehouse locations, loading dock design, and last-mile economics? European models show that smaller, distributed fulfillment hubs near bike-lane networks outperform centralized sorting centers on cost and speed for urban delivery. This will migrate to the US.

The Structural Reality: Two Networks Emerging

For the last 20 years, there was one urban last-mile network: trucks and vans, operating under one set of rules, one cost structure, one infrastructure. That’s the end.

Regulation, economics, and infrastructure all point toward fragmentation. The winners will be operators—whether shippers, carriers, or 3PLs—that build for both networks: a truck/van network for anything beyond two miles, and a bike-lane logistics network for dense urban cores.

The bike-lane network is faster, cheaper, and increasingly legal. It’s not going away. But it’s not a replacement for vans either. The carriers, 3PLs, and shippers that understand this dual reality and execute accordingly will own urban delivery economics. The ones betting everything on one vehicle class will find themselves priced out.

Amazon isn’t inventing cargo quads. Also is. But Amazon is scaling its economics faster than its competitors, which gives it a temporary advantage. That advantage will evaporate once FedEx, UPS, and DHL fully deploy—and they will, because the math is inescapable.

The question for your organization isn’t whether cargo quads work. It’s how fast you can operationalize them and lock in a pricing advantage before the market commoditizes.

Subscribe to FreightFA’s weekly logistics briefing for analysis on carrier strategy, regulatory shifts, and network design implications. Each week, we break down one story that affects your cost structure or competitive position. No fluff—just a signal that moves the needle on your planning.